Happening Now

The Pullman Porters and the Journey to Justice

February 27, 2014

Written By Lessie Henderson

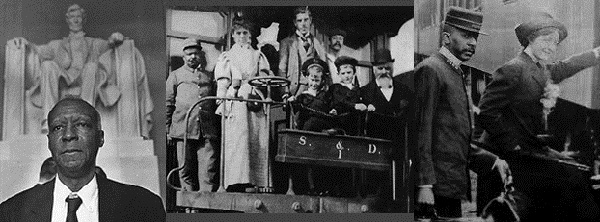

Image courtesy of WTTW Public Media Chicago

In 1867, entrepreneur and industrialist George Pullman had an idea that revolutionized rail travel with the sleeper car. Pullman paid attention to and capitalized on the opportunities in the shift to industrialization and the railroads, which was taking over maritime transport. After a rough and uncomfortable train ride, he envisioned a hotel on wheels where passengers would receive 5-star service and a safe ride, while being cost effective. During the early formation of the Pullman Company, Pullman employed white workers as porters, but he wanted the passengers to have the full service treatment and hospitality. Pullman applied his cost effective model by hiring freedmen from the south—former slaves who had been freed after the Civil War. Pullman believed southern black men would have experience in positions of service; he also said that he thought blacks in the north were “militant” and would not be as obedient or provide the flawless service he envisioned. While these opinions are offensive to the modern sensibility, the Pullman Company provided steady jobs during a time where jobs were scarce for black males; therefore they would be appreciative of working there compared to working in the fields or strenuous labor.

As the demand for the sleeper cars grew as did the number of Pullman Porters, throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many porters became homeowners and were able to support their families, and were highly regarded in their communities. Pullman Porters would refer their younger relatives to the company, creating stability and a rise up the socioeconomic ladder for many families in spite of the low pay. The Pullman sleeper cars were a sign of freedom, income and expanded horizons for many black males. Yet it also served as a reminder of the expectations and stereotypes projected on them daily. Even though they interacted with the leading celebrities and personalities of the day, working for the Pullman Company was anything but glamorous. Porters could not be conductors on the sleeper cars; they were expected to pay for their own uniforms, food and supplies; in addition to the low pay, long hours and discriminatory actions.

Once they traveled below the Mason-Dixon Line into the Jim Crow landscape, the layovers were challenging for porters, and many often slept on benches overnight because they could not stay in the hotels. Black Pullman employees often faced harassment from police officers, and struggled to find restaurants to serve them. Many relied on friends, girlfriends and family in layover cities for food and shelter. Others with no local connections had to bring food so they would not go hungry. Early on, the porters were appreciative of the work despite segregated and harsh work conditions, the attitudes of many of the passengers, and the humiliation being universally referred to as “George”—a sign that they were viewed as nothing more than Pullman’s “boy.” In the company handbooks they were described like rail car equipment, which is how Pullman wanted the porters to appear: clean, unobtrusive, and nonthreatening to the passengers.

After George Pullman’s death in 1897, and President Lincoln’s son Robert Todd took over the company. Many porters were growing discontented with the working conditions, but were still afraid to speak up. Newer generations were becoming porters, however, and they men were a generation removed from slavery, with a different mentality than their elders. During the early 1920’s the railroads expanded during and after the war, the company was still a reliable source of income for many throughout the black community. Some porters held graduate degrees, and many were students looking to earn money during the summer to pay for books and tuition. Some were even doctors and lawyers.

Finally, black Pullman Porters began to organize against the mistreatment, low wages and poor working conditions. Although the company law had to recognize and negotiate with unions by law after labor reforms implemented in the 1920s, the black porters did not benefit from it since the labor unions were still segregated, and efforts to form a union for black workers were blocked for years. This is when the small group of porters knew that they would have to take their efforts to the next level.

The porters summoned labor activist, organizer and civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph during a meeting of 500 porters. Together, they organized into the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in August 1925. At first, just the task of getting their peers mobilized was daunting, as many porters, in spite of harsh conditions, felt strongly loyal to the Pullman Company for its years of stable employment. In addition to the racism blacks already faced with labor unions at the time, they also faced opposition from many local churches. Religious leaders in the black community at the time often opposed affiliation with labor unions, preaching against the notion of “biting the hand that feeds.” Despite this, Randolph would continue to organize porters through membership drives in Chicago, St. Louis and Oakland – the largest train stops in the company– where it gained 51 percent of its members in a single year. The BSCP continued to face challenges with the company and their supporters.

In 1928, The BSCP decided that a strike against the company was the only way to gain attention. After hearing talks of the Pullman Company having replacement workers ready, theunion’s membership declined. Things turned around for the BSCP in 1934 after amendments to the Railway Labor Act granted rights to the group. The BSCP union added approximately 7,000 members after the victory. In 1937, the Pullman Company agreed to a contract and porters finally saw the pay increases, shorter workweeks and other demands come to fruition after years of struggle. The BSCP went on to be a key player in the civil rights movement, connecting with various communities. As passenger rail declined in the 1960’s, membership decreased. As porter runs were cut, focus shifted to other civil rights issues. The BSCP later merged with the Brotherhood of Railway and Airline Clerks (BRAC) into the Sleeping Car Porters Division, which then became a BRAC Amtrak Division in the 1980’s.

Later in Randolph’s life, he served on NARP’s first Advisory Board, helping to shape what the organization represents today: being a national voice for passenger rail and empowering people to be voices for passenger rail throughout their communities. Even as Black History Month winds down, and the story of the Pullman Porters may not reappear until next February, transit advocates should keep in mind the history of the labor movement and the courageous journey of Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and A. Philip Randolph during their advocacy and organizing efforts. Today, many people are joining forces to form groups, coalitions and committees to let local and national leaders know that it is beyond time for equal transportation access and affordability. Even though advocacy efforts can be longand tiring, the story of A. Philip Randolph and the Pullman Porters show that through determination, courage, and organized effort, our goals to improve public transportation are not out of reach.

"Thank you to Jim Mathews and the Rail Passengers Association for presenting me with this prestigious award. I am always looking at ways to work with the railroads and rail advocates to improve the passenger experience."

Congressman Dan Lipinski (IL-3)

February 14, 2020, on receiving the Association's Golden Spike Award

Comments